Mastering Roof Inspections: Underlayment, Part 5

by Kenton Shepard and Nick Gromicko, CMI®

The purpose of the series “Mastering Roof Inspections” is to teach home inspectors, as well as insurance and roofing professionals, how to recognize proper and improper conditions while inspecting steep-slope, residential roofs. This series covers roof framing, roofing materials, the attic, and the conditions that affect the roofing materials and components, including wind and hail.

Climate Types

Climates in North America can be separated into four basic types:

- hot and dry;

- cold and dry;

- hot and humid; and

- cold and humid.

Hot and dry climates will affect bituminous underlayment by accelerating the loss of volatiles.

In humid climates, older felt underlayment will absorb more moisture, which, in turn, can be absorbed by the substrate, causing it to expand.

In cold climates, underlayment will become brittle and more easily damaged by footfall and impact.

Each of these climate types should have underlayment installed which has performance characteristics compatible with that particular climate.

Roof Design

Some designs shed runoff quickly, and some have design features which may actually trap runoff and expose the underlayment to more moisture.

Roof-Covering Material

Manufacturers produce underlayment of different types for use with the different types of roof-covering materials. The use of underlayments that are not compatible with the roof-covering material with which they’re installed can cause problems. You’ll learn more about this in the articles on the individual roof-covering materials.

Roof-covering materials in poor condition which expose underlayment to weather, and especially to UV radiation from sunlight, can accelerate deterioration.

Builder’s Budget

Poor-quality roof-covering materials or installation can affect the long-term service life of underlayment.

Missing Underlayment

Although underlayment is typically required in new construction by building codes, in the past, some manufacturers have not required it on roofs of 4:12 and steeper. Unless you know for certain that the roof-covering material on the home you’re inspecting requires underlayment, you should refrain from calling missing underlayment a defective installation.

Determining whether underlayment is required means finding the manufacturer’s installation instructions for that particular roof-covering material, and also finding out what jurisdictional requirements were in place at the time the home was built.

Since this research falls well beyond the Standards of Practice, you might better serve your clients by making them aware of the steps needed to confirm proper installation, and recommending a qualified roofing contractor.

UNDERLAYMENT INSTALLATION METHODS

Installation methods vary with the pitch of the roof, with the requirements of both underlayment and roof-covering material manufacturers, and with jurisdictional requirements.

One of two fasteners are usually used. Staples are the most common, but in high-wind areas and with synthetics, underlayment is often fastened with plastic caps.

It’s not unusual in areas subject to high winds for roof-covering materials to be blown off but for the underlayment to remain in place.

In these situations, the remaining underlayment can make a big difference in limiting interior water damage. Underlayment fastened with plastic caps instead of staples is more likely to remain in place.

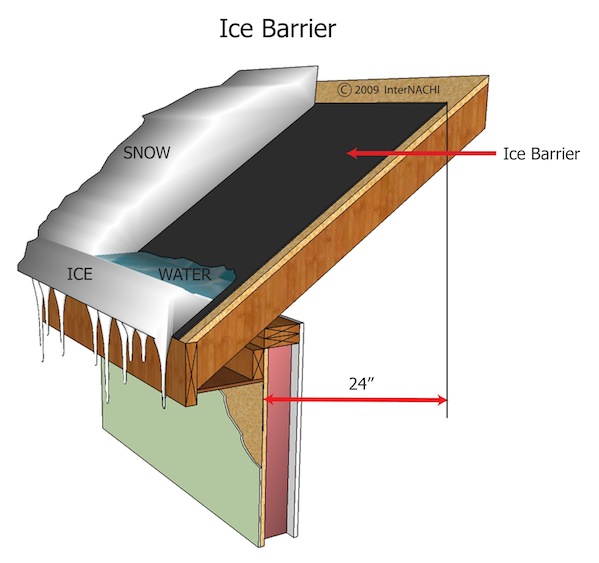

Ice Barriers

In areas where there is a history of ice forming along the eaves, causing melt-water to back up under the shingles (ice dams), ice-barrier underlayment should be installed at the roof edge. An ice barrier is typically a self-sealing, self-adhering waterproof underlayment.

The International Residential Code (IRC) is the residential building code most widely adopted in the US. According to the IRC, the ice barrier should extend from the lower roof edge to a point at least 24 inches in from the outside of the exterior wall, measured level.

All other roofing industry organizations specify that the 24 inches be measured from the inside of the exterior wall.

On roofs with steep pitches, this may result in up to four courses of underlayment. Depending on the roof-covering material and installation method, you may not be able to confirm proper ice-barrier installation. Ice barrier requirements are the same, no matter what roof-covering material is installed.

**************************************************

Learn how to master a roof inspection from beginning to end by reading the entire InterNACHI series: Mastering Roof Inspections.

Take InterNACHI’s free, online Roofing Inspection Course

Mastering Roof Inspections

Roofing Underlayment Types

Inspecting Underlayment on Roofs

Fall-Arrest Systems

Roofing (consumer-targeted)

More inspection articles like this