Introduction

Introduction

This article reviews some fundamental concepts of structural

design and presents them in a manner relevant to the design of light-frame

residential structures. The concepts form the basis for understanding the

design procedures, overall design approach, and how to inspect the structural

design of a residential dwelling. With this conceptual background, it is hoped

that the inspector will gain a greater appreciation for creative and efficient

design of homes, particularly the many assumptions that must be made.

What Is Structural Design?

The process of structural design is simple in concept but

complex in detail. It involves the analysis of a proposed structure to show

that its resistance or strength will meet or exceed a reasonable expectation.

This expectation is usually expressed by a specified load or demand and an

acceptable margin of safety that constitutes a performance goal for a

structure.

The performance goals of structural design are multifaceted.

Foremost, a structure must perform its intended function safely over its useful

life. The concept of useful life implies considerations of durability and

establishes the basis for considering the cumulative exposure to time-varying

risks (i.e., corrosive environments, occupant loads, snow loads, wind loads,

and seismic loads). Given, however, that performance is inextricably linked to

cost, owners, builders, and designers must consider economic limits to the

primary goals of safety and durability.

The appropriate balance between the two competing

considerations of performance and cost is a discipline that guides the art of

determining value in building design and construction. However, value is judged

by the "eye of the beholder," and what is an acceptable value to one person may

not be acceptable value to another (i.e., too costly versus not safe enough or

not important versus important). For this reason, political processes mediate

minimum goals for building design and structural performance, with minimum

value decisions embodied in building codes and engineering standards that are

adopted as law.

In view of the above discussion, a structural designer may

appear to have little control over the fundamental goals of structural design,

except to comply with or exceed the minimum limits established by law. While

this is generally true, a designer can still do much to optimize a design

through alternative means and methods that call for more efficient analysis

techniques, creative design detailing, and the use of innovative construction

materials and methods.

In summary, the goals of structural design are generally

defined by law and reflect the collective interpretation of general public

welfare by those involved in the development and local adoption of building

codes. The designer's role is to meet the goals of structural design as

efficiently as possible and to satisfy a client's objectives within the intent

of the building code. Designers must bring to bear the fullest extent of their

abilities, including creativity, knowledge, experience, judgment, ethics, and

communication aspects of design that are within the control of the individual

designer and integral to a comprehensive approach to design. Structural design

is much, much more than simply crunching numbers.

Load Conditions and Structural System Response

The concepts presented in this section provide an overview

of building loads and their effect on the structural response of typical

wood-framed homes. As shown in the table, building loads can be divided into

two types based on the orientation of the structural actions or forces that

they induce: vertical loads and horizontal (i.e., lateral) loads.

|

Building Loads Categorized by Orientation |

|

Vertical Loads |

Horizontal

(Lateral) Loads |

|

Dead (gravity)

Live (gravity)

Snow (gravity)

Wind (uplift on roof)

Seismic and wind (overturning)

Seismic (vertical ground motion) |

Wind

Seismic (horizontal ground motion)

Flood (static and dynamic hydraulic forces)

Soil (active lateral pressure) |

Vertical Loads

Gravity loads act in the same direction as gravity (downward or vertically) and include dead, live, and snow loads. They are

generally static in nature and usually considered a uniformly distributed or

concentrated load. Thus, determining a gravity load on a beam or column is a

relatively simple exercise that uses the concept of tributary areas to assign

loads to structural elements. The tributary area is the area of the building

construction that is supported by a structural element, including the dead load

(the weight of the construction) and any applied loads (the live load). For

example, the tributary gravity load on a floor joist would include the uniform

floor load (dead and live loads) applied to the area of floor supported by the

individual joist. The structural designer then selects a standard beam or

column model to analyze bearing connection forces (or reactions), internal

stresses (such as bending stresses, shear stresses, and axial stresses), and

stability of the structural member or system. The selection of an appropriate

analytic model is, however, no trivial matter, especially if the structural

system departs significantly from traditional engineering assumptions that are

based on rigid body and elastic behaviors. Such departures from traditional

assumptions are particularly relevant to the structural systems that comprise

many parts of a house, but to varying degrees.

Wind uplift forces are generated by negative (suction)

pressures acting in an outward direction from the surface of the roof in

response to the aerodynamics of wind flowing over and around the building. As

with gravity loads, the influence of wind uplift pressures on a structure or

assembly (such as the roof) are analyzed by using the concept of tributary areas and

uniformly distributed loads. The major difference is that wind pressures act

perpendicular to the building surface (not in the direction of gravity), and

that pressures vary according to the size of the tributary area and its

location on the building, particularly with proximity to changes in geometry (such as at the eaves, corners and ridges). Even though the wind loads are dynamic and highly

variable, the design approach is based on a maximum static load or pressure equivalent.

Vertical forces are also created by overturning reactions

due to wind and seismic lateral loads acting on the overall building and its

lateral force-resisting systems. Earthquakes also produce vertical ground

motions or accelerations that increase the effect of gravity loads. However,

vertical earthquake loads are usually considered to be implicitly addressed in

the gravity load analysis of a light-frame building.

Lateral Loads

The primary loads that produce lateral forces on buildings

are attributable to forces associated with wind, seismic ground motion, floods,

and soil. Wind and seismic lateral loads apply to the entire building. Lateral

forces from wind are generated by positive wind pressures on the windward face

of the building and by negative pressures on the leeward face of the building,

creating a combined push-and-pull effect. Seismic lateral forces are generated

by a structure's dynamic inertial response to cyclic ground movement. The

magnitude of the seismic shear or lateral load depends on the magnitude of

the ground motion, the building's mass, and the dynamic structural response characteristics

(such as dampening, ductility, natural period of vibration, etc.). For houses and

other similar low-rise structures, a simplified seismic load analysis employs

equivalent static forces based on fundamental Newtonian mechanics (F=ma) with

somewhat subjective or experience-based adjustments to account for

inelastic, ductile response characteristics of various building systems. Flood

loads are generally minimized by elevating the structure on a properly designed

foundation or avoided by not building in a flood plain. Lateral loads from

moving flood waters and static hydraulic pressure are substantial. Soil lateral

loads apply specifically to foundation wall design, mainly as an "out-of-plane" bending load on the wall.

Lateral loads also produce an overturning moment that must

be offset by the dead load and connections of the building. Therefore,

overturning forces on connections designed to restrain components from rotating

or to keep the building from overturning must be considered. Since wind is capable of

generating simultaneous roof uplift and lateral loads, the uplift component of

the wind load exacerbates the overturning tension forces due to the lateral

component of the wind load. Conversely, the dead load may be sufficient to

offset the overturning and uplift forces, as is often the case in lower design

wind conditions and in many seismic design conditions.

Structural Systems

As far back as 1948, it was determined that conventions in

general use for wood, steel and concrete structures are not very helpful for

designing houses because few are applicable, according to the National Bureau of Standards

(NBS). More specifically, the NBS document encourages the use of more

advanced methods of structural analysis for homes. Unfortunately, the study in

question and all subsequent studies addressing the topic of system performance

in housing have not led to the development or application of any significant

improvement in the codified design practice as applied to housing systems. This

lack of application is partly due to the conservative nature of the engineering

process, and partly due to the difficulty of translating the results of

narrowly-focused structural systems studies to general design applications. But

this document is narrowly scoped to address residential construction design.

If a structural member is part of a system, as is typically

the case in light-frame residential construction, its response is altered by

the strength and stiffness characteristics of the system as a whole. In

general, system performance includes two basic concepts known as load-sharing

and composite action. Load-sharing is found in repetitive member systems (including wood framing) and reflects the ability of the load on one member to be shared

by another, or, in the case of a uniform load, the ability of some of the load

on a weaker member to be carried by adjacent members. Composite action is found

in assemblies of components that, when connected to one another, form a "composite member" with greater capacity and stiffness than the sum of the

component parts. However, the amount of composite action in a system depends on

the manner in which the various system elements are connected. The aim is to

achieve a higher effective section modulus component than members taken separately.

For example, when floor sheathing is nailed and glued to floor joists, the

floor system realizes a greater degree of composite action than a floor with

sheathing that is merely nailed; the adhesive between components helps prevent

shear slippage, particularly if a rigid adhesive is used. Slippage due to shear

stresses transferred between the component parts necessitates consideration of

partial composite action, which depends on the stiffness of an assembly's connections. Therefore,

consideration of the floor as a system of fully composite T-beams may lead to

an non-conservative solution, whereas the typical approach of only considering

the floor joist member without composite system effect will lead to a

conservative design.

The information presented here addresses the strength-enhancing effect of load-sharing and partial composite action when information is available for

practical design guidance. Establishment of repetitive-member increase factors

(also called system factors) for general design use is a difficult task because

the amount of system effect can vary substantially depending on system assembly

and materials. Therefore, system factors for general design use are necessarily

conservative to cover broad conditions. Those that more accurately depict

system effects also require a more exact description of and compliance with

specific assembly details and material specifications.

It should be recognized, however, that system effects do not

only affect the strength and stiffness of light-frame assemblies (including

walls, floors, and roofs). They also alter the classical understanding of how

loads are transferred among the various assemblies of a complex structural

system, including a complete wood-framed home. For example, floor joists are

sometimes doubled under non-load-bearing partition walls because of the

added dead load and resulting stresses determined in accordance with

accepted engineering practice. Such practice is based on a conservative

assumption regarding the load path and the structural response. In other words, the

partition wall does create an additional load, but the partition wall is

relatively rigid and actually acts as a deep beam, particularly when the top

and bottom are attached to the ceiling and floor framing, respectively. As the

floor is loaded and deflects, the interior wall helps resist the load. Of

course, the magnitude of effect depends on the wall configuration, including the amount

of openings and other factors.

This example of composite action due to the interaction

of separate structural systems or sub-assemblies points to the improved

structural response of the floor system such that it is able to carry more dead

and live loads than if the partition wall were absent. One whole-house assembly

test performed in 1965 demonstrated this effect. Hence, a double joist should

not be required under a typical non-load-bearing partition; in fact, a single

joist may not even be required directly below the partition, assuming that the

floor sheathing is adequately specified to support the partition between the

joists. While this condition cannot yet be duplicated in a standard analytic

form conducive to simple engineering analysis, the designer should be aware of

the concept when making design assumptions regarding light-frame residential

construction.

At this point, the inspector should consider that the response

of a structural system, and not just its individual elements, determines the manner

in which a structure distributes and resists horizontal and vertical loads. For

wood-framed systems, the departure from calculations based on classical

engineering mechanics (such as single members with standard tributary areas and

assumed elastic behavior) and simplistic assumptions regarding load path can be

substantial.

Load Path

Loads produce stresses on various systems, members, and

connections as load-induced forces are transferred down through the structure

to the ground. The path through which loads are transferred is known as the

load path. A continuous load path is capable of resisting and transferring the

loads that are realized throughout the structure from the point of load

origination down to the foundation.

As noted, the load path in a conventional home may be

extremely complex because of the structural configuration and system effects

that can result in substantial load-sharing, partial composite action, and a

redistribution of forces that depart from traditional engineering concepts. In

fact, such complexity is an advantage that often goes overlooked in typical

engineering analyses.

Furthermore, because interior non-load-bearing partitions are

usually ignored in a structural analysis, the actual load distribution is

likely to be markedly different from that assumed in an elementary structural

analysis. However, a strict accounting of structural effects would require

analytic methods that are not yet available for general use. Even if it were

possible to capture the full structural effects, future alterations to the

building interior could effectively change the system upon which the design was

based. Thus, there are practical and technical limits to the consideration of

system effects and their relationships to the load path in homes.

The Vertical Load Path

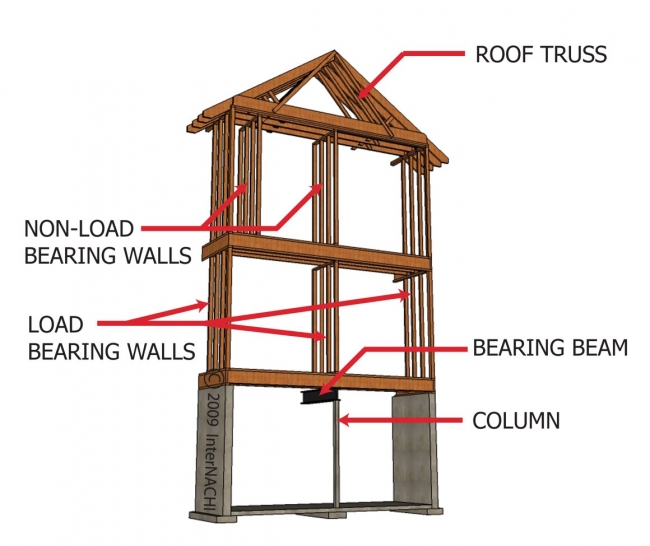

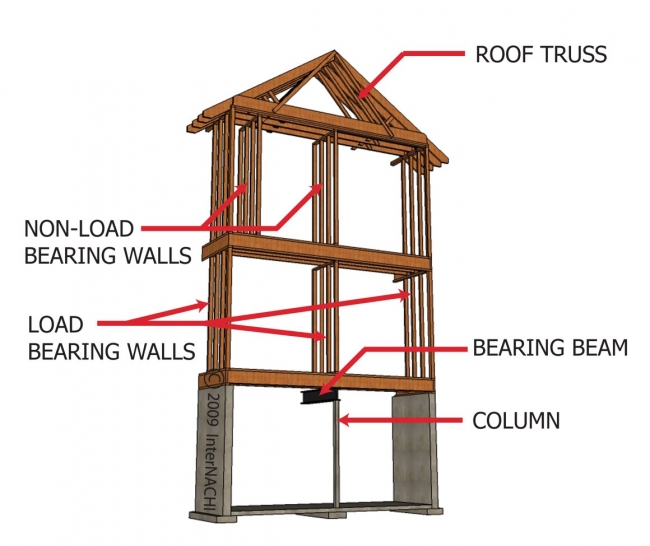

Figures 1 and Figure 2 below illustrate vertically-oriented loads

created, respectively, by gravity and wind uplift. It should be noted that the

wind uplift load originates on the roof from suction forces that act

perpendicular to the exterior surface of the roof, as well as from internal

pressure acting perpendicular to the interior surface of the roof-ceiling

assembly in an outward direction. In addition, overturning forces resulting

from lateral wind or seismic forces create vertical uplift loads (not shown in

Figure 2). In fact, a separate analysis of the lateral load path usually

addresses overturning forces, necessitating separate overturning connections

for buildings located in high-hazard wind or seismic areas. It may be feasible

to combine these vertical forces and design a simple load path to accommodate

wind uplift and overturning forces simultaneously.

Figure 1. Illustration of the

Vertical Load Path for Gravity Loads

Figure 2. Illustration of the

Vertical Load Path for Wind Uplift

In a typical two-story home, the load path for gravity loads

and wind uplift involves the following structural elements:

- roof sheathing;

- roof sheathing attachment;

- roof framing member (rafter or truss);

- roof-to-wall connection;

- second-story wall components (top plate, studs,

sole plate, headers, wall sheathing, and their interconnections);

- second-story-wall-to-second-floor connection;

- second-floor-to-first-story-wall connection;

- first-story wall components (same as second

story);

- first-story-wall-to-first-floor or foundation

connection;

- first-floor-to-foundation connection; and

- foundation construction.

From this list, it is obvious that there are numerous

members, assemblies, and connections to consider in tracking the gravity and

wind uplift load paths in a typical wood-framed home. The load path itself is

complex, even for elements such as headers that are generally considered simple

beams. Usually, the header is part of a structural system (see Figure 1), rather than an individual element single-handedly resisting the entire load originating

from above. Thus, a framing system around a wall opening, and not just a header,

comprises a load path.

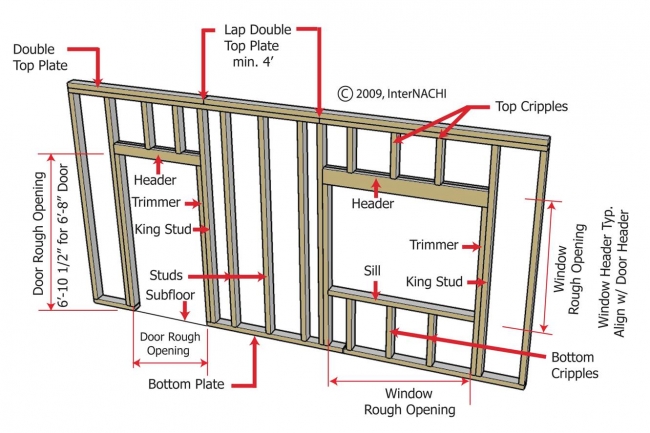

Figure 3. Illustration of Wall and Window Framing Components

Figure 1 also demonstrates the need for appropriately

considering the combination of loads as the load moves "down" the load path.

Elements that experience loads from multiple sources (e.g., the roof and one or

more floors) can be significantly over-designed if design loads are not

proportioned or reduced to account for the improbability that all loads will

occur at the same time. Of course, the dead load is always present, but the

live loads are transient. Even when one floor load is at its lifetime maximum,

it is likely that the others will be at only a fraction of their design load.

Current design load standards generally allow for multiple transient load

reductions. However, with multiple transient load reduction factors intended

for general use, they may not effectively address conditions relevant to a

specific type of construction, such as residential.

Consider the soil-bearing reaction at the bottom of the

footing in Figure 1. As implied by the illustration, the soil-bearing force is

equivalent to the sum of all tributary loads, dead and live. However, it is

important to understand the combined load in the context of design loads. Floor

design live loads are based on a lifetime maximum estimate for a single floor

in a single level of a building. But in the case of homes, the upper and lower

stories or occupancy conditions typically differ. When one load is at its

maximum, the other is likely to be at a fraction of its maximum. Yet, designers

are not able to consider the live loads of the two floors as separate transient

loads because specific guidance is not currently available. In concept, the

combined live load should therefore be reduced by an appropriate factor, or one

of the loads should be set at a point-in-time value that is a fraction of its

design live load. For residential construction, the floor design live load is

either 30 psf (for bedroom areas) or 40 psf (for other areas), although some

codes require a design floor live load of 40 psf for all areas. In contrast,

average sustained live loads during typical use conditions are about 6 psf

(with one standard deviation of 3 psf), which is about 15% to 20% of the

design live load, according to Chalk and Corotis (1980). If actual loading conditions are

not rationally considered in a design, the result may be excessive footing

widths, header sizes, and so forth.

When tracking the wind uplift load path (Figure 2), the

designer must consider the offsetting effect of the dead load as it increases

down the load path. However, it should be noted that building codes and design

standards do not permit the consideration of any part of the sustained live

load in offsetting wind uplift, even though it is highly probable that some

minimum point-in-time value of floor live load is present if the building is in

use, such as when it is furnished and/or occupied. In addition, other non-engineered load

paths, such as provided by interior walls and partitions, are not typically

considered. While these are prudent limits, they help explain why certain

structures may not "calculate" but otherwise perform adequately.

Depending on the code, it is also common to consider only

two-thirds of the dead load when analyzing a structure's net wind uplift

forces. The two-thirds provision is a way of preventing the potential error of

requiring insufficient connections where a zero uplift value is calculated in

accordance with a nominal design wind load (as opposed to the ultimate wind

event that is implied by the use of a safety margin for material strength in

unison with a nominal design wind speed). Furthermore, code developers have

expressed a concern that engineers might over-estimate actual dead loads.

For complicated house configurations, a load of any type may

vary considerably at different points in the structure, necessitating a

decision of whether to design for the worst case or to accommodate the

variations. Often, the worst-case condition is applied to the entire structure

even when only a limited part of the structure is affected. For example, a

floor joist or header may be sized for the worst-case span and used throughout

the structure. The worst-case decision is justified only when the benefit of a

more intensive design effort is not offset by a significant cost reduction. It

is also important to be mindful of the greater construction complexity that

usually results from a more detailed analysis of various design conditions.

Simplification and cost reduction are both important design objectives, but

they may often be mutually exclusive. However, the consideration of system

effects in design, as discussed earlier, may result in both simplification and

cost efficiencies that improve the quality of the finished product.

One helpful attribute of traditional platform-framed home

construction is that the floor and roof gravity loads are typically transferred

through bearing points, not connections. Thus, connections may contribute

little to the structural performance of homes with respect to vertical loads

associated with gravity (dead, live, and snow loads). While outdoor deck

collapses have occurred on occasion, the failure in most instances is

associated with an inadequate or deteriorated connection to the house, and not a

bearing connection.

By contrast, metal plate-connected roof and floor trusses

rely on connections to resist gravity loads, but these engineered components

are designed and produced in accordance with a proven standard and are

generally highly reliable. Indeed, the metal plate-connected wood

truss was first conceived in Florida in the 1950s to respond to the need for improved

roof structural performance, particularly with respect to connections in roof

construction.

In high-wind climates where the design wind uplift load

approaches the offsetting dead load, the consideration of connection design in

wood-framed assemblies becomes critical for roofs, walls, and floors. In fact,

the importance of connections in conventionally built homes is evidenced by the

common loss of weakly attached roof sheathing or roofs in extreme wind events, such as moderate-to large-magnitude hurricanes.

Newer prescriptive code provisions have addressed many of

the historic structural wind damage problems by specifying more stringent

general requirements (SBCCI; AF&PA). In many cases, the newer high-wind

prescriptive construction requirements may be improved by more efficient

site-specific design solutions that consider wind exposure, system effects, and

other analytic improvements. The same can be said for prescriptive seismic

provisions found in the latest building codes for conventional residential

construction (ICC; ICBO).

Lateral Load Path

The overall system that provides lateral resistance and

stability to a building is known as the lateral force-resisting system (LFRS).

In light-frame construction, the LFRS includes shear walls and horizontal

diaphragms. Shear walls are walls that are typically braced or clad with

structural sheathing panels to resist racking forces. Horizontal diaphragms are

floor and roof assemblies that are also usually clad with structural sheathing

panels. Though more complicated and difficult to visualize, the lateral forces

imposed on a building from wind or seismic action also follow a load path that

distributes and transfers shear and overturning forces from lateral loads.

The

lateral loads of primary interest are those resulting from:

- the horizontal component of wind pressures on

the building's exterior surface area; and

- the inertial response of a building's mass and

structural system to seismic ground motions.

As seen in Figure 3, the lateral load path in wood-framed

construction involves entire structural assemblies (including walls, floors, and

roofs) and their interconnections, not just individual elements or frames, as

would be the case with typical steel or concrete buildings that use discrete

braced framing systems. The distribution of loads in Figure 3's

three-dimensional load path depends on the relative stiffness of the various

components, connections, and assemblies that comprise the LFRS. To complicate

the problem further, stiffness is difficult to determine due to the

non-linearity of the load-displacement characteristics of wood-framed assemblies

and their interconnections. Figure 4 below illustrates a deformed light-frame

building under lateral load; the deformations are exaggerated for conceptual

purposes.

Figure 4. Illustration of the

Lateral Load Path

Figure 4. Illustration of

Building Deformation under Lateral Load

Lateral forces from wind and seismic loads also create

overturning forces that cause a "tipping" or "roll-over" effect. When these

forces are resisted, a building is prevented from overturning in the direction

of the lateral load. On a smaller scale than the whole building, overturning

forces are realized at the shear walls of the LFRS such that the shear walls

must be restrained from rotating or rocking on their base by proper connection.

On an even smaller scale, the forces are realized in the individual shear wall

segments between openings in the walls. As shown in Figure 3, the overturning

forces are not necessarily distributed as might be predicted. The magnitude and

distribution of the overturning force can depart significantly from a typical

engineering analysis depending on the building or wall configuration.

The overturning force diagrams in Figure 3 are based on

conventionally built homes constructed without hold-down devices positioned to

restrain shear wall segments independently. It should be noted that the effect

of dead loads that may offset the overturning force and of wind uplift loads

that may increase the overturning force is not necessarily depicted in Figure 3's

conceptual plots of overturning forces at the base of the walls. If rigid-steel

hold-down devices are used in designing the LFRS, the wall begins to behave in

a manner similar to a rigid body at the level of individual shear wall

segments, particularly when the wall is broken into discrete segments as a

result of the configuration of openings in a wall line.

Summary

In summary, significant judgment and uncertainty attend the

design process for determining building loads and resistance, including

definition of the load path and the selection of suitable analytic methods.

Designers are often compelled to comply with somewhat arbitrary design

provisions or engineering conventions, even when such conventions are

questionable or incomplete for particular applications such as a wood-framed

home. At the same time, individual

designers are not always equipped with sufficient technical information or

experience to depart from traditional design conventions. Therefore, this information serves as a resource for both inspectors and designers who are

considering the installation and use of improved analytic methods when current

analytic approaches may be lacking.

Introduction

Introduction