Inspection Reports: Engage Your Senses

Inspectors are “details” people. They deal in facts. They deal in what they can see. That’s the very definition of the job. So, it would seem that, for most inspectors, their confidence in recognizing defects would translate just as easily into their inspection reports. But writing, in general, can be intimidating. For many inspectors, report writing constitutes the most writing they’ve ever done, and calls to bear their sometimes minimal skills in that area. Even for the naturally gifted or most enthusiastic writers, the act is fraught with its usual difficulties, including problems with spelling, punctuation and grammar, that often slip through the net of the average word-processing program.

Observe and Report

Many inspectors advertise that their reports are “easy to understand.” That’s the beauty of good writing. It is simple, but it includes observational details that are dense yet clearly written. For example, your gut may tell you that there is something seriously wrong with a roof when you first poke your head over the top of the ladder. But when you actually inspect it up close, you can see exactly why it’s not in good condition. Those are the details that you can relate in your report:

- There was a standing puddle where the slopes intersect on the west side of the roof, but it hasn’t rained in more than 48 hours.

- The tiles on the roof surrounding the puddle were darker, indicating that the moisture was extended.

- While depressing four tiles outside the perimeter of the puddle, they became detached from the roof’s underlayment.

- There was a musty smell, indicating possible onset of mold growth.

- The attic vent fan operated intermittently instead of continuously; heard scraping noise of fan blades against metal.

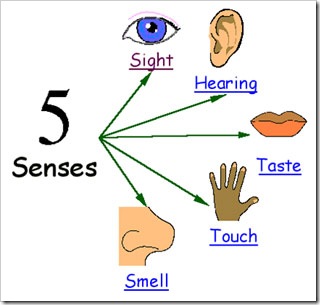

You're probably more adept at inspecting using your five senses than you're consciously aware of. The trick is to integrate that information into your report using language that reflects the observational details that your senses produce.

Observation vs. Opinion

One weakness of reports that lack detailed observations is that the information sounds more like an opinion. “The roof is in good condition” is arguably the opinion of the inspector, but that type of statement is all too often the sort of default language that is wide open to interpretation. And that leaves the inspector wide open to liability. Even if your client accompanied you on parts of your inspection, and even if you were confident in your findings and explanations that you verbally conveyed to him, you can’t assume that he shares your perspective, knowledge or insight (or even that he remembered everything you said).

EXAMPLE:

Your Recommendations

The observational details that you record will then inform your recommendations, which will give your client a next step, and even a roadmap to recovery:

- Roof’s condition indicated issues related to moisture intrusion, as evidenced by presence of standing water, and weakened tile adhesion to underlayment.

- Recommend further investigation by a roofing contractor.

- Recommend further investigation by a roofing contractor.

- Musty smell indicated possible onset of mold growth.

- Recommend further investigation to include mold testing and possible mitigation.

- Recommend further investigation to include mold testing and possible mitigation.

- Attic vent fan operated intermittently instead of continuously; heard scraping noise of fan blades against metal.

- Recommend further investigation and repair or replacement.

- Recommend further investigation and repair or replacement.

How Good Is Your Product?

Your client may follow you around for parts of your inspection, and you may be able to show him many problems as you discover them. You can educate him by explaining their significance, imparting the wisdom of your experience and expertise. This is the service you provide as an inspector, and this is also part of the overall service-ethic that we encourage at InterNACHI. It’s one of the things that sets InterNACHI inspectors apart. But the product of your inspection is not two hours on a Tuesday afternoon. It’s your inspection report. A great inspection report is dense with relevant observational details.