Inspecting Stair Stringers

by Nick Gromicko and Ben Gromicko

According to the InterNACHI® Home Inspection Standards of Practice (www.nachi.org/sop), the home inspector is required to inspect the stairs, steps, landings, and stairways. The following information is about a load-bearing component of the stairway that is usually not readily visible and beyond the scope of a visual-only home inspection – the stair stringer. Understanding the components of a stairway, including the stringers, may help a home inspector do a better job.

The image below is of a cut stringer, a common but a mostly hidden component of an interior finished stairway.

Home Inspection Standards of Practice

During a home inspection, the stair stringers are usually covered up, and therefore not observed and not inspected. A home inspection report shall identify, in written format, defects within specific systems and components defined by the Home Inspection Standards of Practice that are both observed and deemed material by the inspector. The home inspection will not reveal every issue that exists or ever could exist, but only those material defects observed by the inspector on the date of the inspection.

Code

Structural performance issues of stair stringers in residential buildings can result in problems ranging from cracking of the cosmetic finish and vibrations to major structural failures, which can result in severe injuries. Despite those issues, there are a lot of general rule-of-thumb recommendations but very few specific prescriptive code construction provisions for wood-framed stair stringers in residential buildings.

Stair stringers should meet the general construction standards except where amended by the local jurisdiction. The International Residential Code (IRC) and the International Building Code (IBC) contain few provisions regarding wood-framed stair stringer design and construction. Most of the code provisions describe dimension minimums and maximums for width, rise, run, and vertical height. There are limited dimensional constraints for residential interior stair construction. Therefore, it's mostly left to the builder's or contractor's knowledge, experience, and the rules-of-thumb they follow in relation to stair stringers.

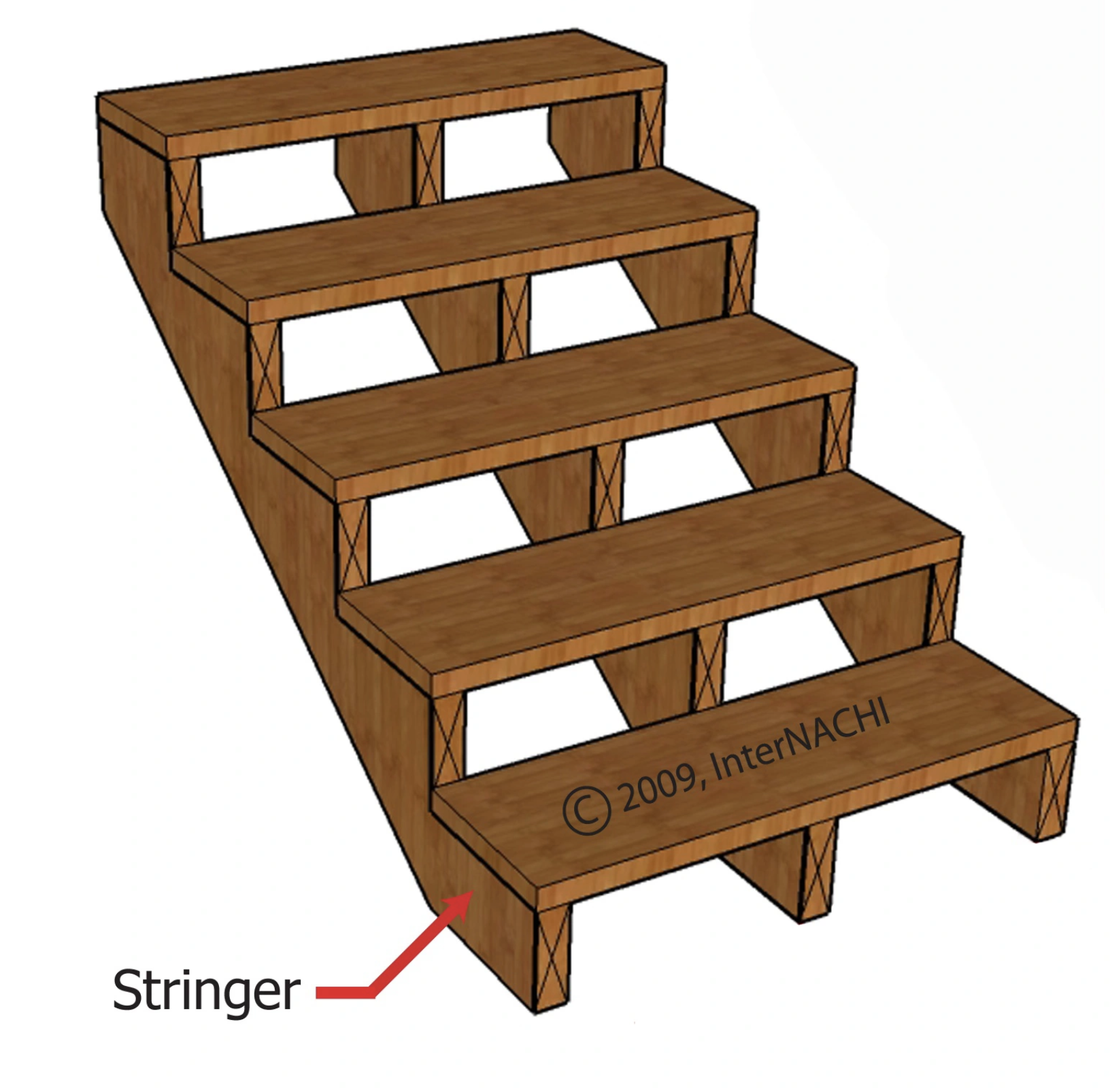

Stair Stringer

The stair stringer is a structural member installed on either side or in the center of a flight of stairs into which the treads and risers are attached. The primary function of the stringer is to provide a framework and load-bearing support for the treads and risers.

According to the 2018 IRC, R311.7.5, the riser height maximum is 7-3/4 inches (196 mm). That is measured vertically between the leading edges of the adjacent treads. The tread depth must be at least 10 inches (254 mm). See the illustration above. That is measured horizontally between the vertical planes of the foremost projection of the adjacent treads at a right angle to the tread's leading edge. These tread and riser dimensions directly affect the size of the stringer board, the throat dimensions of a cut stringer, and the amount of board remaining beneath the tread-riser piece that was removed. The throat depth is the net depth of a stringer once the steps are cut and removed, and it is measured from the step perpendicular to the bottom edge of the stringer.

Building Process

Stairs inside a house are often built by two different contractors. Framers will cut stringers from 2x12-inch boards or sometimes laminated veneer lumber (LVL), and then attach rough treads for temporary use during the home's construction. A finish carpenter will later remove the rough treads and install finished treads, risers, and inner and outer skirt boards. Some finish carpenters prefer to remove the entire rough stairway and build a housed-stringer stairway that has treads and risers fitted and glued into routed dadoes of closed, solid stringers. And the stringers and treads could be made from 5/4-inch- thick boards of pine, poplar, oak, or Douglas fir. The information presented here covers 2x12-inch board stringers.

Types of Stringers

There are two common types of stringers for stairs in residential buildings. The first type is the cut stringer, sometimes referred to as the open or sawtooth stringer, whose treads are exposed when viewed from the side of the stairway. This stringer is cut open with the rise and run measurements. Some carpenters refer to this type of stringer as a carriage because it exposes the treads and risers. The second type is the closed stringer, sometimes referred to as routed, housed, boxed, solid, or side stringers, whose treads are contained in between the stringers. Closed stair stringers can have notches or dadoes into which the treads and risers can be inserted. Closed stair stringers hide the tread edge. A third and less common type of stringer the mono stringer that acts more like a large centrally located beam in what is referred to as a beam stairway.

Stringers may be made of solid wood lumber, pressure-treated lumber, timber, LVL, and many other types of building materials as well. Steel and aluminum stairways are less common in residential buildings. Boards, stair treads, guards, and handrails for exterior decks and stairways are often made of plastic composite materials.

Another term used for the stringer is a carriage. There are some sources that define the stringer as the component that encases the treads and risers, and a carriage is the component that exposes the treads and risers. Carriage and stringer are mostly used interchangeably.

Cleats are small pieces of wood that act like small ledger boards installed underneath the ends of the treads on an uncut stringer. Cleat stairs are dangerous if the cleats are not made of substantial size or strength, and if not fastened properly. Cleat stairs or ledger stairs may not be permitted in some areas.

Stairway Width

Each of the three key components related to egress – the egress door, hallways, and stairways – have minimum widths. The width of the stairway can determine the number of stairway stringers that should be installed.

Stairways must be at least 36 inches (914 mm) in width, but there are exceptions. When the building code specifies a required width, it is in reference to the clear, net, usable, unobstructed width. However, in relation to stairways, the width minimum is in relation to only the area above the permitted handrail height and below the required headroom height (2018 IRC, R311.7.1). At and below the handrail height, the required width of the stairway, including treads and landings, is only 27 inches (686 mm) if handrails are installed on each side, and only 31-1/2 inches (800 mm) if there is only one handrail installed. Inspectors do not need to be concerned about trim, stringers, or other items that may be found below the level of the handrail, as long as they do not exceed the handrail's projection. Spiral stairways can be as narrow as 26 inches (660 mm). So, in general, the typical stairway is 36 inches wide.

The number of stringers installed at a wood-framed stairway is related to the 36-inch minimum width. If cut stringers are used in the stair construction, then at least three stringers are required. Cut stringers should be spaced no more than 18 inches on center. For example, a 36-inch-wide stairway should have three stringers.

If the stairway is wider than 36 inches, four stringers should be installed. If the stairs are wider than 36 inches (914 mm), a combination of cut and solid stringers can be used, but the maximum spacing between the stringers should be 18 inches (457 mm) on center. The maximum 18-inch spacing works well with treads made of 2x boards or 5/4-inch boards.

2x12-Inch Stringers

The rough-framed stair stringers made from solid wood lumber are often made of 2x10-inch or 2x12-inch dimensional lumber boards.

Some stair stringers may be sistered with 2x4-inch boards in order to strengthen a 2x10-inch stringer that has only 3-1/2 inches of board remaining beneath the tread-riser notch. An undersized stringer may also be over-spanned, of poor-quality wood, and may also have knots, cracks, or other defects that weaken the stringer board.

Carpenters may add an uncut, unnotched stringer board to the outside of a cut stringer to strengthen it. A cut stringer is significantly weaker than a closed stringer; therefore, it may be necessary to reinforce it with an uncut stringer or LVL beam.

Span of Stringers

Stair stringers should not span more than 13 feet and 3 inches (4039 mm) for a closed stringer.

Cut stringers should not span more than 6 feet (1829 mm).

Refer to the American Wood Council's 2018 Prescriptive Residential Wood Deck Construction Guide for stringer spans. If the stringer span exceeds these dimensions, then a support (such as a knee wall) should be provided to shorten the stringer span's length. An intermediate landing may be installed to shorten the stringer span.

Refer to the American Wood Council's 2018 Prescriptive Residential Wood Deck Construction Guide for stringer spans. If the stringer span exceeds these dimensions, then a support (such as a knee wall) should be provided to shorten the stringer span's length. An intermediate landing may be installed to shorten the stringer span.

Load

Stairways should be able to adequately hold up a live load. Live loading is specified as 40 pounds per square foot for residential applications. Individual stair treads in homes shall be designed for the uniformly distributed live load of 40 pounds per square foot, 100 pounds per square foot for other applications (IBC Table 1607.1), or a 300-pound concentrated load acting over an area of 4 square inches, whichever produces the greater stresses. (2018 IRC, Table 301.5).

Stairway Vertical Height

The 2021 IRC, R311.7.3, states that a flight of stairs shall not have a vertical rise greater than 12 feet and 7 inches (3835 mm or 151 inches) between floor levels or landings. The code also states that there are exceptions to this vertical height limit. They are: (a) stairways not within or serving a building, porch, or deck; (b) stairways leading to non-habitable attics; and (c) stairways leading to crawlspaces.

The 2021 IBC, Section 1011.8, states that a flight of stairs should not have a vertical rise greater than 12 feet (3658 mm or 144 inches). The vertical height is measured from one landing's walking surface to another.

It is ultimately up to the local authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) to apply specific provisions from particular codes. Usually, the most restrictive provision is preferred and applied. In cases where different codes (IRC and IBC, for example) have different requirements for the same specific application (the stairway's vertical height, for example), the most restrictive requirements take precedence.

Carpeting

All of the stairway dimensions in the building code are exclusive of carpets, rugs, and runners. Stair covers are often changed by homeowners and are not incorporated into the code. It is important that the tread and landing surfaces are consistent and comply with the code prior to the addition of carpet.

The IRC does not require solid risers, but in a flight of stairs, any riser opening that is located more than 30 inches above the floor below must not allow the passage of a 4-inch-diameter sphere.

Connections

A critical issue for wood-framed stair construction is the connection of the stair stringer to the supported structure connected to the stairway. Fitted into notches at the bottom of the stringer boards, there is often a thrust block, cleat, or kicker board to prevent movement. The full bearing of the bottom of the stringer should be supported. If it's not, then a structural crack may develop.

There are various ways that the top of the stair stringers could be attached to the structure or stairwell header, and that is where a serious failure can occur. The top of the stringers could be flush-framed to a header. The floor or landing header could serve as the top riser. The top tread could be flush to the top finished floor. Some may use a plywood hanger, ledger board or a nailer. If the tops of the stair stringers are dropped down from the landing or floor level, then there must be a doubled header or adequate framing components to which the tops of the stringers will connect. End-nailing the stringers through the header boards is not recommended because of the possibility of withdrawal. Dropping the stringers without also installing a dropped header can lead to the stringers having an inadequate bearing on the rim joist.

Failures at the stairway stringer connections could be sudden and catastrophic. There is a history of occupants and firefighters getting fatally injured from collapsing stairways. Some installers will use lag bolts. Some stringers may only be nailed at the top. Stringer ends should not be end-nailed or toe-nailed.

The 2018 IRC Table R602.3(1) and 2018 IBC Table 2304.10.1 offer specifications on how a joist connects with a header or girder. These connection provisions cannot be applied directly to stair stringer boards, but the 2018 IRC, Section R311.5.1, states, "Attachment shall not be accomplished by use of toe nails or nails subject to withdrawal." This refers to stairs, decks, and other building elements. Because of the complex forces acting upon a set of stairs, nails may be subject to withdrawal when used to mount the top head of a set of stringers.

The most cost-effective way to hang a stringer is with metal hardware. Mechanical connections with sloped sawn lumber face-mount hangers should be installed. They are simple to use and are capable of handling the connection forces. The stringer must be fully seated or bearing on the mechanical connector seat. And the correct type of fasteners must be used with the mechanical hardware. Deck and drywall screws instead of approved connector fasteners are sometimes used to fasten the connector to the framing, which is a major defect.

Notching and Overcutting

Notching dimensional lumber to build cut stringers (see illustration below) is a common practice that takes into consideration only the depth of wood beneath the tread-riser notches as effective in resisting the applied load. For cut stringers, care should be taken not to overcut the limits of the notch. Overcutting notches in stringers is a major defect.

Overcutting of notches in the stair cut stringer at the tread-riser intersection is a common major defect caused by unskilled or careless carpenters. Overcutting weakens the stringer's overall strength by reducing the effective depth of the stringer member. The resulting throat of the stringer should not be less than the prescribed throat, which, for a 2x12, is approximately 5 inches. See illustration below.

For example, a typical wood-framed stair stringer may have 15 risers. Each riser may be cut at 7¼ inches in height, with 10-1/2-inch-long treads, but the unit rise and unit run measurements will depend upon the total rise and total span of the staircase. See illustration below.

The stringers are commonly cut of 2x10-inch or 2x12-inch boards made of spruce-pine-fir (SPF) or LVL. This configuration results in an effective throat depth on a 2x12-inch cut stringer of approximately 5 inches, and a total horizontal stringer span of 12 feet and 3 inches.

The stringers are commonly cut of 2x10-inch or 2x12-inch boards made of spruce-pine-fir (SPF) or LVL. This configuration results in an effective throat depth on a 2x12-inch cut stringer of approximately 5 inches, and a total horizontal stringer span of 12 feet and 3 inches.

The uniformity of risers and treads is a safety factor in any flight of stairs, inside or outside the home. The maximum variation between the highest and lowest risers is limited to 3/8-inch (9.5 mm). Variations in excess of the 3/8-inch tolerance could interfere with the rhythm of the stair user. The most common location for a large variation between riser height is at the landings. The finish framer often needs to make adjustments to the rough stringers in order to meet this tolerance.

Deflection

Deflection is the degree to which an element of a structure changes shape when a load is applied. When a load produces a deflection on a stringer that is too great, the component may fail. Structural systems and members must be designed to have adequate stiffness to limit deflection. Deflection limits are needed for the comfort of the occupants and so that the structural member's deflection does not cause damage to other components of the supporting construction. Deflection also helps reduce cracking of wall finishes (such as drywall cracks in the corners near the stairs).

The deflection of stair stringers is mostly ignored by builders in typical residential construction, but code limits should be applied. Deflection criteria are listed in the 2018 IBC Table 1604.3 and 2018 IRC R301.7. According to these tables, the most applicable limits for stair stringers are L/360 for live loads and L/240 for total loads.

What L/360 means is that when you know the load criteria provided by code, the live load deflection of that member is limited to 1/360th of the span. To use a very simple example, a floor joist that is 360 inches in length would be permitted to deflect (sag) a maximum of 1 inch.

The second number – the L/240 – is the total load, which is the live and dead loads added together. If the floor joist's live load deflection limit is L/360, the total load deflection limit is typically L/240. That means that the 360-inch floor joist would be allowed to have a total load deflection of 1-1/2 inches.

Plastic Composite

For an exterior stairway, plastic composite deck boards, stair treads, guards, and handrails may be used and must be installed in accordance with the locally adopted code and the manufacturer’s instructions. According to the 2018 IRC, Section R507.2.2.1, plastic composite deck boards, stair treads, guards, and handrails for exterior decks, or the packaging, should have labeling that indicates compliance with ASTM D7032. The labeling should describe the allowable load and maximum allowable span. Each deck board and stair tread, similar to pressure/preservative-treated wood, is required to have a label.

Deck board labels should identify the allowable load and span. For example, 40 psf load on a 16-inch (406 mm) span would be expressed as “16/40” on the label. The spacing of stringers for plastic composite treads may be as little as 9 inches apart.

Summary

The home inspector is required to inspect the stairs, steps, landings, and stairways, but much of the structural components of an interior finished stairway are hidden and beyond the scope of a home inspection. Understanding how a stairway is built may help a home inspector do a better job.

References:

- American Wood Council, Prescriptive Residential Wood Deck Construction Guide, 2018

- Wood-framed Stair Stringer Design and Construction, Christopher R. Fournier, P.E., 2013

- Stair Stringers and Treads, Specifier's Guide, Weyerhaeuser, February 2019

- Stair Stringer Technical Guide, Tolko, October 2018

- Bruce Parker, Common Deck Stair Defects, Journal of Light Construction, July 2017

- International Residential Code (IRC), 2018 and 2021

- International Building Code (IBC), 2018 and 2021

Read More:

"How to Inspect the Attic, Insulation, Ventilation and Interior" Course