Inspecting Floating Homes

by Nick Gromicko, CMI® and Kenton Shepard

Figure 1: A floating home built on a concrete barge using train cars

There are some types of homes that don’t fit neatly into any category. They’re unusual, and that’s what attracts many people to them. Floating homes are one of these types.

Each state defines floating homes differently, but in general, they’re:

- constructed on a float;

- designed and built to be used as a residential dwelling;

- stationary by being moored or anchored, and not meant for navigation;

- without a means of self-propulsion;

- powered by utilities connected to the shore; and

- permanently and continuously connected to a sewage system on shore.

The definition of a floating home varies according to the jurisdiction where a home is located, which is important because jurisdictions often have regulations with which such homes must comply. Regulations are also different for similar structures, such as house barges and houseboats.

House Barges

House barges are vessels that are designed to be navigable; that is, they’re meant to move around, but not under their own power. They’re meant to house people, but they’re also meant to be towed. If they become permanently moored or anchored, they may have to comply with regulations that govern floating homes. House barges are fairly rare and many jurisdictions do not allow new ones.

Houseboats

Houseboats must have a seaworthy hull design that meets U.S. Coast Guard standards for flotation, safety equipment, fuel, electrical power, ventilation, and an on-board sewage system. They’re capable of being used for water transportation, and if they’re used for residential purposes, they have to be able to travel under their own power and must have a method for steering and propulsion, as well as deck fittings, navigational and nautical equipment, and the required marine hardware. Without these features, they’re categorized as house barges.

Floating Homes

Figure 2: Floating homes docked in slips and one moored on the bay

Floating homes are generally required to be moored in areas designated for that purpose, and in many areas, the growth of such “floating communities” is discouraged by local jurisdictions. Cities and towns tend to view them as cluttering the waterways and they present unique problems requiring special efforts, which puts pressure on limited city budgets.

Where they’re allowed, they’re usually moored alongside docks with projections called slips. To moor a floating home is to attach it to a dock or permanent anchor with ropes instead of a rigid connection. This allows the home to rise and fall with the tide or seasonal changes in water levels and puts less stress on permanent docks and mooring anchors.

Figure 3: A typical method for mooring at a slip

Figure 4: Ramps that provide access to slips or boats are typically hinged at the top

and have rollers or wheels at the bottom to allow for changes in water level.

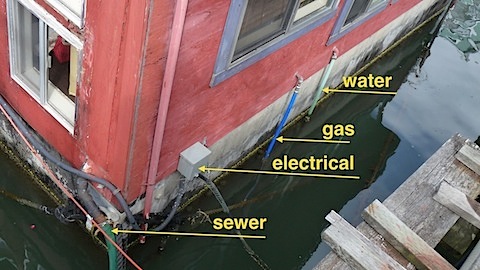

Although some floating home communities allow slips to be sold, the slip facility or marina is typically owned by a company that rents the slips out. In most places, homes are subject to property tax, which helps defray the cost of police and fire department services. In some states, such as Oregon, homes are taxed as personal property, so no tax is paid on the land. Slip rental prices are usually figured by the linear foot. A management company maintains the slip facilities for which there is usually an additional monthly fee. The marina may be responsible for providing some utilities, such as potable water, natural gas, electrical power, and/or sewage. In some areas, the homeowner must contract directly with the utility provider. Gas, water and sewer pipes and electrical power lines are suspended from the undersides of docks and branch out to homes in each slip.

Sewage handling is worth mentioning. Each home has what’s called a “honey pot,” properly called a macerator. This is a tank in the 30- to 50-gallon range with a mechanism that grinds sewage down to about 1/16-inch, with a pump that pumps it ashore through a flexible hose. Inexpensive honey pots may last only a couple of years, and replacing them is an expensive and unpleasant chore. Stainless steel is a good choice for tank material.

Sewer pipes in modern systems are connected to the public sewer system. Smaller marinas sometimes have a main holding tank that may be connected to the public sewer system, or it may require pumping.

Figure 5

Figure 6

In northern communities, such as Portland and Seattle, frozen water pipes can be a problem, so pipes above the waterline should be insulated. A similar problem can happen in homes with high-efficiency furnaces. Condensate drainage pipes usually discharge out the side of the home into the water. In cold climates, the pipe can freeze over and condensate will start to discharge into the part of the home where the furnace is located, which can be a mess. It can be a smelly mess if condensate winds up in the bilge and items start to decay.

In most floating home communities, the dock facilities are usually in good condition, such as in the photo below.

Figure 7

There are exceptions. In older communities, such as this low-income co-op, conditions may be quite different.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Floats

Obviously, floating homes are built on flotation devices, and there are a number of different types. Modern home flotation devices are usually concrete barges, logs, foam, or foam-filled steel. Steel pontoon floats are sometimes filled with foam. A few older homes may still rest on hollow plywood floats that have been coated with fiberglass. These can suffer from decay caused by fresh water intrusion from above. Any plywood floats you see are likely to be old and can be dangerous. While log floats and concrete barges fail slowly, plywood floats may fail catastrophically, causing the home to suddenly sink.

Figure 12: A concrete barge waiting for the home

Concrete barges are able to float because of the large amount of water they displace. They’ve been around since about the 1940s. If concrete of the proper strength is used (approximately 4,000 PSI), barges may fail mainly through corrosion of the steel reinforcement bar (rebar). Construction of modern barges includes a grid of #4 (1/2-inch) rebar in the walls and bottom, and additional #5 and #6 rebar at key locations, such as in the bottom and corners and along the top of the wall. Until around the late 1990s, rebar was installed uncoated, which limited the service life of concrete barges to about 40 years. Rebar is now coated with epoxy, which extends the expected service life considerably. Fusion-bonded epoxy, which is applied in powder form and turns molten at between about 350° to 480° F, can be applied to rebar, creating a barge that can last hundreds of years. As of 2011, prices for new concrete barges were around $71 per square foot. Some concrete hulls have been constructed using weaker mix designs that are more appropriate for land-based foundations. These barges can deteriorate more quickly than those built using a proper mix.

Barge exteriors are painted with polyurethane epoxy. Over time, this epoxy coating will be deteriorated by weather, slowly exposing more of the concrete, as you see in the photo below.

Figure 13: It’s not necessary to clean the bottom,

and doing so may damage the epoxy coating.

In older barges, this means that any steel close to the surface may be exposed to the corrosive effects of salt water because concrete is porous. Any cracks that develop can also expose rebar to salt water, so, when examining the barge, cracks that show rust are a bad sign. Repair involves cleaning out the crack and filling it with an appropriate material.

Figure 14: A crack showing rust means that rebar is corroding.

An inspector should recommend repair.

Figure 15: This photo shows a diagonal crack with no rust. No rust means no corrosion,

so there is no need for repair unless the crack grows and begins to rust.

Cracks can develop several different ways. As with most concrete structures, concrete barges will have shrinkage cracks, but these are surface cracks that appear not long after the barge material is first poured and will be filled when the epoxy coating is applied to the hull exterior. Shrinkage cracks are not a concern because they are a function of the natural curing process.

In some areas, floating homes will rest on the bottom at low tide. This can create stresses that can contribute to cracking. In areas where homes rest on the bottom at low tide, the bottom quickly conforms to the shape of the boat. The exception is when an object of some type is buried in the mud or sand beneath the barge. This object might be part of an old boat, or part of an old dock, such as a piling. This situation can create point loads that can damage the hull.

Positive Flotation

Some concrete hulls are constructed with a large cavity in the bottom filled with expanded polystyrene foam. This gives the hull positive flotation, so even if a breach of the hull were to develop, unlike a concrete barge, the hull with foam will not sink. After being placed in the cavity, the foam is covered over with a cementicious material.

For financing and insurance reasons, the difference between a concrete hull with or without positive flotation can be important, so when inspecting or buying a floating home with a concrete hull, be sure to look at the documentation to find out whether concrete barge construction includes positive flotation.

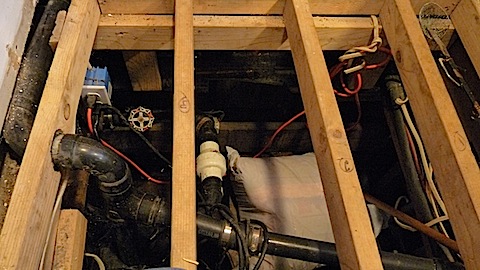

Another way to recognize hulls with positive flotation is that a concrete barge has a bilge. The bilge is the space beneath the floor framing of the home. Some jurisdictions may require a hull without positive flotation to have a bilge pump, which is very similar to a float-activated sump pump. In a positive flotation concrete float, the space beneath the floor is also filled with foam.

Figure 17

Entering the space beneath the floor can be difficult or impossible without taking invasive measures. In the photo below, the access hatch is located beneath the upper stair landing at the left.

Livable spaces in floating homes may be created in one of two ways. A home may be built on the float or barge, or an existing boat may be mounted on either one.

Figure 19: A home built directly on a concrete barge

Figure 20: A home built by mounting a boat on a concrete barge

Figure 21: Here you can see the shoring supporting the boat

until the deck is framed in around it.

Boats are loaded onto barges by sinking the barge in deeper water, floating the boat over the barge, and then raising the barge beneath the boat.

Figure 22: Decking being constructed around a boat hull resting on a concrete barge

Figure 23: Sometimes, custom barges are built to the shape of the boat hull.

Expanded Polystyrene Billets

Homes may rest on rectangular chunks of closed-cell expanded polystyrene (EPS) foam, which will not absorb water. Since the 1990s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers requires that all foam used in marine (salt water) environments be encapsulated. It’s more common for EPS foam to be used for adjusting the trim of floating homes than as the primary flotation method.

Log Floats

You may also see logs used as floats. This is traditional in the Pacific Northwest because of the timber industry located there. The photo below shows logs being moved into place for a houseboat that is being converted into a floating home. According to the photographer, the cost of these logs was about $1,000 each.

Figure 24

(Courtesy of Scott Niesen)

Homes rest on stringers that, in turn, rest on the log floats. Logs are typically notched to accept the stringers. Ripping logs, such as those you see in the photo below, provide a flat surface on which the stringers can rest, which makes stringer placement easier and makes the logs essentially self-leveling.

Figure 25: Logs ripped to accept stringers

(Courtesy of Scott Niesen)

Figure 26: Logs notched to accept stringers

(Courtesy of Scott Niesen)

Figure 27: Log floats with epoxy-coated steel stringers

(Courtesy of Jane Betts-Stover)

Figure 27.1: This diagram shows typical construction methods for a log float.

(CLICK HERE for hi-res version)

Because there are no standards for the inspection of floats, items inspected and commented on in reports may vary.

Here are items commonly inspected during the float inspection of a log float home:

- mooring connections: Some jurisdictions have minimum requirements for chains and chain plates. Mooring connections that are too loose may allow the float or home to rub and wear against the dock or slip.

- logs: Describe the approximate diameter of the logs, their quantity, and mention any splices. Describe the degree to which decay has taken place. One of the requirements for decay to take place is the presence of oxygen. Since water contains little oxygen, the underwater portions of logs deteriorate much more slowly than the portions above water. Since end-grain absorbs water more easily, some decay may take place there also. Logs may last up to 75 years. Logs for floats are sometimes reclaimed from older homes and installed in newer homes, so logs should be checked for uniformity of condition.

- flotation: If additional flotation has been added, the adequacy of its condition and location should be commented upon. Because trim flotation often has to be added due to changing weight distribution when a new occupant moves their belongings aboard, commenting on the space available for additional flotation is a good idea. Also mention whether adding flotation will increase the draft. The draft is the depth of the float structure beneath the waterline. Contractors specializing in adjusting trim with flotation can usually make changes in less than an hour.

- stringers: Describe the material of which the strings are made and their nominal size. If they’re wood, find out if it’s pressure-treated wood. If they’re steel, find out if they have an adequate protective coating.

- floor structure: What is the nominal size and spacing of the floor joists? Are they structurally adequate? Was pressure-treated wood used? Was pressure-treated wood/plywood used for the sub-floor? Is the floor insulated?

- deck condition: For recreation and for access to the home exterior, many homes have exterior decks that project out from one or more sides of the home. The deck’s structural support, framing and planking should be inspected for corrosion and decay.

Figure 27.2: Floatation for decks and docks may be different from that of

floating homes.

Potential Requirements and Limitations

When inspecting floating homes, inspectors and consumers should be aware of the local jurisdiction’s requirements and limitations for the following.

Jurisdictions

- minimum freeboard: “Freeboard” is the distance between the waterline and the lowest portion of the house. The minimum varies with jurisdiction and is often somewhere between 12 and 16 inches.

- maximum list: To list is to tilt. A floating home should sit parallel to the waterline. If a home is constructed or is loaded with the occupant’s belongings in such a way that the weight is unevenly distributed, the home may list. The maximum list allowable can vary with location but may be in the neighborhood of 6 degrees, or 2 inches overall. In some circumstances, foam flotation can be placed beneath the home to correct a list.

- Check any local height limitations.

- Check whether there’s a limit on the number of dwellings that can use a single float or barge.

- Some jurisdictions may require that the float be durable to the satisfaction of a marine surveyor or professional engineer, meaning that it may not be not subject to deterioration by water, mechanical damage due to floating debris, electrolytic action, water-borne solvents, organic infestation, or physical abuse, Jurisdictions, lenders and/or insurance companies may require inspection of the float, including the underwater portion, at specified time intervals. Inspection may need to be performed by a diver qualified to inspect floats, or by a marine surveyor.

- Jurisdictions and marinas may have setback or other requirements that limit additional construction on or expansion of an existing floating home.

Marinas

- Marinas may have limitations on the number of non-family members who can share a floating home.

- Slips may be difficult to find. If for some reason a homeowner loses a slip, it may be difficult to find a marina in the desired area that has room for another boat.

Moorings

- Floating homes in communities located on rivers may rise and fall as much as 25 feet as seasonal water levels change. At extremely low water levels, such as might occur during drought years, homes with too deep a draft due to added flotation may go aground. Boats with log floats are generally not designed to rest on the bottom, and the torque created by unintended contact with the bottom can cause damage. When this happens, as soon as increasing water levels make it possible, areas of the river bottom where the floats have made contact will be excavated, or flotation will be removed.

- Floating homes move. Homes may be moved by strong winds that blow them across the water until they reach the end of the mooring lines, which stop them with a jerk. Wakes from passing boats can also move homes. This can be a concern if someone is on a ladder or can throw small children aboard off balance.

- Gangways or ramps serve as means of egress and should have a non-skid surface or cleats. They may also have to meet minimum width or maximum slope regulations.

Inspection

Utilities

- Electrical installations installed near the water may need to meet special requirements for wet environments.

- Overhead service drops may have to meet height minimums from walkable surfaces beneath.

- Water service connections may require back-flow preventers and flexible connections.

- Are any water distribution pipes above the waterline insulated?

Mortgages and Insurance

The ease of finding a lender for a floating home varies with the area. Established communities usually have at least one lender, although rates may be a little higher, and they often want 20% to 25% down. Seller financing is sometimes available. The availability of insurance also varies with location and may be expensive. Both a mortgage and insurance may be easier to find if the home is located in a jurisdiction that has standards with which floating homes must comply.

Figure 28: A contrast in quality

The home in the photo above rests on expanded polystyrene floats, some of which are encapsulated and some of which are not. The front doorstep leaves something to be desired.

The covered entry of the home in the photo below is attached to the home and will rise and fall with the tide. This home is located in an area where the floats rest on the bottom at low tide, so a minimum headroom clearance could be calculated.

Figure 29

Figure 30: Wood in a marine environment