by Nick Gromicko, CMI® and Kate Tarasenko

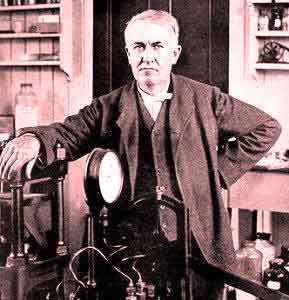

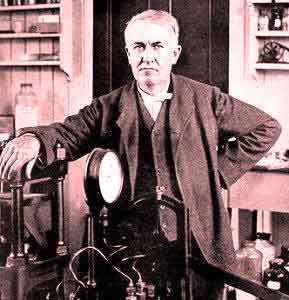

Many electricians, history buffs and schoolchildren know that Thomas Edison is credited with inventing the lightbulb. In fact, his role in this instance was improving upon a concept that was already 50 years old. What Edison did that left his mark on the invention was to develop a safe, practical and affordable incandescent electric light for use in the home, as well as for commercial applications.

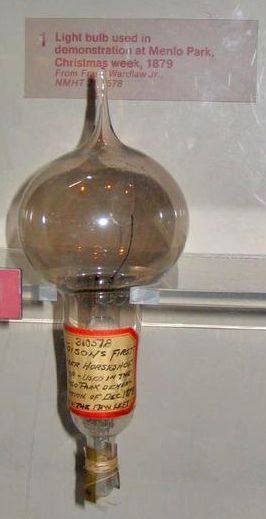

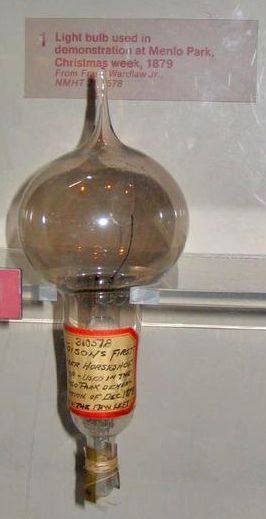

After much trial and error, by 1879, Edison created an electric light using a small glass globe with a carbonized filament of sewing thread, and just the right amount of vacuum inside the bulb, powered by a low electric current. His new lightbulb burned for more than 12 hours before the filament burned out.

Once Edison hit upon the right combination of elements that made up his new bulb, the question lingered as to how to power it properly. The first-ever centralized power plant was still three years away from operation, and this delay led to some interesting, if not hazardous, demonstrations of electrically powered light.

One of Edison’s patrons was American business tycoon William Henry Vanderbilt, whose family built the New York Central Railroad. Vanderbilt insisted that Edison equip the parlor in his home with lightbulbs, which were powered by a generator that was installed in the basement for the purpose. The lights burned well, if briefly, during the evening, when a near-tragedy occurred that was probably routine in Edison’s day-to-day world of inventing, but could very well have derailed the course of history as we know it. Edison’s own notes described the scene:

“Mr. Vanderbilt, his wife and some of his daughters came in and were there a few minutes when a fire occurred. The large picture gallery was lined with silk cloth interwoven with fine metallic tinsel. In some manner, two wires had got crossed with tinsel, which became red-hot, and the whole wall was soon afire.”

The problem, it was soon realized, was that the wiring was not properly insulated. When the hot wiring made contact with the tinsel in the wallpaper, it burst into flames.

The fire was quickly extinguished and there were no injuries. Unfortunately for Mr. Vanderbilt, the hysterical Mrs. Vanderbilt, upon being told that the generator used to power the bulbs was located in the basement, insisted on its removal. She refused to spend another night in the home until her demand was met. Her alarm was misplaced – the generator itself was perfectly safe -- but Mr. Vanderbilt was forced to relent and removed it. It’s not known when Mrs. Vanderbilt allowed her household to again be illuminated with electric light.

An electric distribution system that could provide safe, sustained and affordable power to home- and business-based electric lights would prove to be the next greatest challenge on the road to electricity, but, because of Edison's early wild successes (the Vanderbilt parlor fire notwithstanding), and the almost instantaneous consumer demand, this next technological development was on the fast track.

The first centralized power plant went online in 1882. Located on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan, it served 59 homes with 110 volts, costing its customers about 24 cents per kilowatt-hour. The power station burned 10 pounds of coal per hour, the equivalent of about 138,000 BTUs.

By the end of the decade, small central power stations sprang up in all the major cities of the U.S., serving an area of only a few blocks each because of the power inefficiencies of direct current. Overhead wiring came next, in 1883. Electrical safety and performance-testing methods were also high on Edison's to-do list. The “Wizard of Menlo Park,” as he was known (owing to his nearly 1,100 patents in the U.S. alone), was largely responsible for developing the innovations that expanded electricity to both homes and industry, ultimately transforming the modern world.

Inspecting the electrical system is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of a home inspection, followed closely by potential hazards while walking a roof. Inspectors checking out the electrical system of a residence must take safety precautions to guard against accidental electrical shock, not to mention the odd electrical fire. Inspectors also must check for faulty components, overloaded receptacles, trip hazards owing to extension cords, and also for proper insulation of the wiring both within the home and at the exterior service. Guard against these dangers by reviewing InterNACHI's Residential Standards of Practice, and by preparing adequately for your inspection.