Constituent Materials of Concrete

Concrete is a composite material consisting of a binder, which is typically cement, rough and fine aggregates, which are usually stone and sand, and water. These comprise the constituent materials of concrete. But because of the many variables of the raw materials and how they are processed and combined, there are many opportunities for problems to appear in concrete. Having a fundamental understanding of the different materials and manufacturing processes may help those who inspect concrete to know what problems to look for, where to look for them, and how to recognize them.

In simple terms:

- cement + water = cement paste;

- cement paste + sand = mortar; and

- mortar + stone = concrete.

Admixtures may be included in the mix to control setting properties.

The chemical reactions that take place when different constituent materials are combined can vary depending on the properties of the individual materials. The materials can vary in their chemical makeup and performance characteristics, depending on where they were mined or quarried, and according to the manufacturing methods used and conditions in the manufacturing plant.

Binders

Binders are fine, granular materials that form a paste when water is added to them. This paste hardens and encapsulates aggregates and reinforcement steel. Immediately after water is added, cement paste begins to harden through a chemical process called hydration. Hydration takes place at different rates according to the different properties of the binders and admixtures used, the water-to-cement ratio, and the environmental conditions under which the concrete is placed. The ways in which binders affect concrete, mortar and similar products can vary with the chemical and physical properties of the source materials, the constituent materials, the mix design, and, to a lesser extent, the variations in the cement manufacturing process.

Portland Cement

Portland cement

There are different types of cement, but Portland cement is the binder used most widely. Although Portland cement is named after an area in England where its use was originated, today it is manufactured all over the world.

ASTM International defines Portland cement as “hydraulic cement (cement that forms a water-resistant product) produced by pulverizing clinkers consisting essentially of hydraulic calcium silicates, usually containing one or more of the forms of calcium sulfate as an inter-ground addition.”

Portland cement is made by fusing calcium-bearing materials with aluminum-bearing materials. The calcium may come from limestone, shells, chalk, or marl, which is a soft stone, or hard mud, sometimes called mudstone, that is rich in lime.

The Cement Manufacturing Process

The basic operations of cement plants are roughly similar but may vary according to location. The manufacturing process that follows describes what takes place in a quarry and cement plant in Colorado.

Quarry Operations

A limestone layer about 18 feet thick breaks the surface and slants away underground. Quarrying operations follow it down to a level of about 200 feet before it is no longer profitable to pursue.

The dark-colored rock pictured above contains limestone and two kinds of shale, all of which are used in producing cement. The light-colored material is called over-burden, which is not used in manufacturing, but is set aside to be replaced later during reclamation after the quarry has reached the end of its permit period and is closed.

The flat area in the quarry wall, called the lift or bench, is the depth to which holes are drilled before charges are set for blasting. Here, it is about 80 feet. Because of Homeland Security requirements, most quarries subcontract the blasting operations.

After blasting, the waste stone is brought to the end of the quarry where quarrying first began. It will be the first material to be filled back in as part of the reclamation process. Usable stone is hauled by truck and either dumped into the primary crusher or piled nearby.

The roads and piles must be kept watered to reduce airborne dust.

Trucks back into this building to dump their loads into the primary crusher.

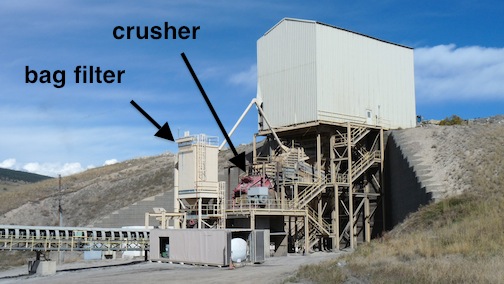

The primary crusher

After the stone is dumped into the feed chute from above, gravity moves it down through the crusher, which reduces it to about 3 inches in diameter. A bag filter helps reduce airborne dust.

From the crusher, the stone moves onto a conveyor belt that carries it to the manufacturing plant about 2 miles away.

Long conveyor belts must be kept adjusted to the proper tension. This is done by using steel cables to suspend concrete weights inside the towers.

At each point where the conveyor changes height or direction, another bag filter helps to remove dust from the crushed stone and from the air.

The limestone and shale are finally stockpiled at the far end of the production line.

The stone is loaded with a front-end loader one bucketful at a time onto a conveyor that carries it into the surge silo (above left). From the surge silo, the stone can be conveyed into the system at a uniform rate. From the surge silo, the stone is transported to a dryer that removes most of the moisture before returning it to the secondary crusher (center silo), where it is reduced to about 3/8-inch in diameter. From this point, the stone is transported by high-speed air instead of by roller-supported belts.

The dried, crushed stone is then moved to the ball mill, in which tumbling steel balls reduce it to a powder. The ball mill is a spinning cylinder that has a sacrificial lining held in place by hundreds of bolts, the heads of which can be seen in the photo above.

Different materials are combined in the ball mill, so this is also where initial blending takes place. Common materials are limestone, shale, sandstone and iron.

From the ball mill, the material moves to the pre-heat tower (at left), where it is heated to about 1,800° F before moving to the horizontal, cylindrical, rotating kiln.

The kiln (dark grey) is tilted slightly so that the material moves through it as it rotates. The more steeply inclined tube above the kiln (light grey) supplies combustion air, as does the U-shaped duct at the top of the pre-heat tower. Inside the kiln, the material is heated to about 3,300° F. This process is called sintering. Chemical changes take place that result in the formation of a marble-sized substance called clinker. Creating clinker means using heat to drive all carbon dioxide out of the material. Carbon dioxide is a major greenhouse gas.

The photo above shows the doors open at the lower end of the kiln, which is shut down for inspection and service. The 6-inch-diameter flexible pipe slanting down to the left is the gas supply for the burner that ignites the pulverized coal fuel. The end of the 8-inch coal supply pipe can be seen just to the right of the feet of the worker.

Stockpiles of the pulverized coal used to fuel the kiln

Clinker is moved to a specially-shaped storage shed to control its moisture content.

Clinker is finely ground to create the final cement product. The photo above shows both the marble-sized clinker before being ground, and the final product: cement.

The entire operation is monitored and controlled from a central control console that contains numerous monitors with real-time digital readouts.

Variations

Although there are ASTM standards with which Portland cement may comply, there are a number of factors that can cause its performance characteristics to vary.

Particle Size

The size of the particles is important because particles that are ground more finely offer more surface area against which the chemical reactions take place, and these strongly influence the properties of the cement. Cement with small particles will be more reactive and will gain strength sooner after the hydration process has begun. The total surface area of the particles in a given volume of material is called its specific surface.

Portland cements have a specific surface of 1,500 to 2,000 square feet per pound of material (ft2/lb), equal to around 300 to 400 square meters per kilogram (m2/kg), depending on type.

Gypsum and Sulfates

Gypsum, also in the form of ground particles, is mixed with the ground clinker to slow the hydration process enough so that there will be time to place the concrete, screed it, and finish it before it sets. If gypsum or sulfate materials are added to and ground with the clinker material, they may be reduced in size more quickly than the clinker. This preferential grinding can result in smaller particles, which increases their ratio of reactivity compared to that of the clinker material.

For any particular cement, there is an optimum content for both gypsum and sulfate. The details of exactly how sulfates affect the strength development of concrete are not well understood.

The optimum content of both gypsum and sulfates depends not only on the type of cement design mix, but also on the:

- chemical properties of both the calcium and aluminum source materials used for the clinker;

- physical properties of the aluminates, such as crystal size;

- varying solubility of the different sources of the sulfates;

- particle size;

- milling temperature; and

- use of admixtures.

As if this weren’t complicated enough, the optimum sulfate content for one cement property, such as strength, may be different from the optimum content for another property, such as drying shrinkage. Concrete and mortar can have different optimum contents, which is why different types of cements are manufactured.

Materials are tested four times during the manufacturing process in an effort to prevent such problems. The raw materials are tested before they enter the manufacturing process, before entering the kiln, after leaving the kiln, and before final storage in the main storage silos.

Cement wafers used in a portion of the testing process

Equipment used to test compressive strength

Cement Types

ASTM Specification C-150 provides standards for eight different types of Portland cement:

- Type I is a general-purpose cement used in a wide variety of project types, including buildings, bridges, floors, pavements, and precast concrete projects.

- Type IA is similar to type I but is used for projects requiring air-entrainment.

- Type II generates less heat, generates heat at a slower rate, and has moderate resistance to sulfate attack.

- Type IIA is identical to Type II but is used for projects requiring air-entrainment.

- Type III is a high early-strength cement that causes concrete to set and gain strength quickly. Type III cement is chemically and physically similar to Type I except that the particles are more finely ground.

- Type IIIA is a high early-strength cement used for projects requiring air-entrainment.

- Type IV develops strength at a slower rate than other cement types and produces lower levels of heat during hydration. It’s used for large-mass concrete structures from which there is little chance for heat to escape, such as dams.

- Type V is used only in concrete structures that will be exposed to severe attack by sulfates, typically in places where concrete is exposed to soil and groundwater with a high sulfate content.

ASTM C-1157 includes the following:

- Type GU hydraulic cement is used for general construction.

- Type HE is high early-strength cement.

- Type MS is moderately resistant to attack from sulfates.

- Type HS is highly resistant to attack from sulfates.

- Type MH produces moderate levels of heat during hydration.

- Type LH produces low levels of heat during hydration. This cement type can also be designed for low reactivity (Option R) with alkali-reactive aggregates.

SUPPLEMENTARY CEMENTICOUS MATERIALS

Pozzolans

Other materials may be blended with Portland cement to meet special requirements and environmental considerations. Some of these materials, called pozzolans, do not have cementicious properties until mixed with Portland cement. When concrete is mixed, in order to improve its workability and flow characteristics, more water is added beyond what is needed for hydration. This surplus water is then present in tiny capillary channels in the hydrated (hardened) concrete. When a pozzolan material is substituted for a portion of the cement, a secondary chemical reaction takes place after hydration. Chemicals released from the cement paste during hydration react with chemicals in the pozzolan material to form a material that partially or fully fills these capillary channels. This makes concrete more dense and increases its resistance to chemicals (such as those used for de-icing operations) that can penetrate porous concrete and corrode reinforcement steel and cause surface deterioration or spalling.

Surface spalling caused by de-icing chemicals

When a portion of the cement is replaced with pozzolans, less heat is produced during hydration. This secondary reaction produces some heat, but the peak temperatures are lower and spread out over a longer period of time. Since concrete contracts (shrinks) as it cools, less heat means less overall shrinkage. Since shrinkage creates stresses that are relieved by cracking, less shrinkage means fewer cracks. This is especially important with high-mass structures that cannot release heat easily, such as dams.

Fly Ash

Flay ash viewed at the microscopic level

Fly ash is an industrial by-product that is sometimes used as a partial replacement for Portland cement. Fly ash is composed of the non-combustible particulates that are removed from the flue gas of coal-burning power plants. It may form up to 65% of the mass of cementicious materials, depending on the performance requirements of the concrete and the type of coal burned.

Reclaiming fly ash for industrial use is an environmentally sound practice, since fly ash is removed from flue gas to improve air quality, and its use in cement means that what was once a waste product is now recycled as a useful material. As of 2005, U.S. coal-fired power plants reported producing 71 million tons of fly ash, 29 million tons of which were used in various applications. The remaining 42 million tons could cover an acre of land to a depth of 27,500 feet. This unused fly ash takes up space in landfills and contains toxins that can contaminate aquifers. In December 2008, an embankment at a Tennessee Valley Authority fly ash storage facility in Kingston, Tennessee, failed and released 5.4 million cubic yards of fly ash into the Emory River. Cleanup costs are approaching $1.2 billion.

Failure of a fly ash containment facility in Kingston, Tennessee

Here are some relevant facts about fly ash used in concrete:

- Fly ash comes in types F and C. Type F fly ash is made by burning older, harder coal. It is a pozzolan and when mixed with water, does not produce cementicious compounds unless the mix includes Portland cement. Type C is made by burning younger, softer coal and does have some cementicious compounds when it’s mixed with water.

- Very fine particles of fly ash can improve the flow characteristics of concrete, reduce costs by replacing cement, require less water in the mix, and make concrete more dense. Coarse particles do not provide the same benefits, and coarse and fine particles cannot always be separated effectively.

- It may increase the setting time.

- Fly ash does not accept pigments or acid stains as well as cement, so matching existing concrete made without fly ash can be a problem.

- The performance characteristics of fly ash vary with particulate size, but also with the chemical composition of the coal, the degree to which the coal is pulverized before burning, the combustion conditions in the furnace, and fly ash collection and handling methods. Since these factors are never the same in different power plants, and may even change within one power plant over time, the properties of fly ash can vary widely, and this can be a barrier to getting consistently good results.

- Fly ash has a specific surface of 1,400 to 3,400 ft2/lb (280 to 700 m2/kg), depending on type.

Ground, Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag

Blast-furnace slag clinker before grinding

Ground, granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBFS) is another industrial by-product sometimes used as a partial replacement for Portland cement. GGBFS is a glassy, granular material produced in blast furnaces as a by-product of the iron and steel-making process. It is another example of a material that used to be considered waste being put to good use.

Compared to concrete made with only Portland cement, concrete that includes GGBFS:

- hardens more slowly;

- produces less heat during hydration;

- continues to gain strength for a longer period of time; and

- produces more durable concrete.

The lower temperatures produced by GGBFS during hydration allow control joints to be placed farther apart. GGBFS is substituted 1-to-1 with Portland cement, and may form up to 70% of the mass of cementicious materials. GGBFS has a specific surface of 1,700 to 2,900 ft2/lb (350 to 600 m2/kg).

Silica Fume

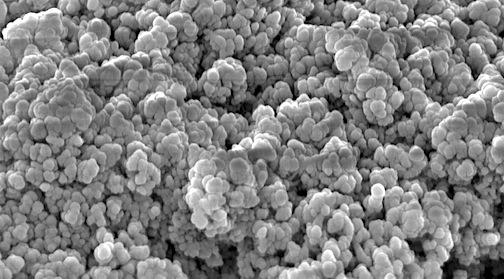

Silica fume magnified 10,000 times

Silica fume is sometimes used to enhance certain properties of concrete. It is a very fine, glass-like powder collected from the flue gases of electric arc furnaces during the process of manufacturing silicon metals. Before the implementation of tougher environmental laws in the mid-1970s, silica fume was not collected. It has now become one of the most valuable and versatile concrete admixtures in the world. Unlike sand – its chemically similar counterpart – particles of silica fume are water-soluble, which means that they can react chemically as part of the hydration process.

When the amounts of two granular materials are equal, materials with smaller particles expose more surface area against which reactions can take place. Silica fume is approximately 100 times smaller than Portland cement particles, and so its small size, along with its relatively high silica content, make it a very highly reactive pozzolan. Their small particle size also allows silica fume to fill in the spaces between grains of cement, called particle-packing, making concrete more dense and less porous or permeable to moisture. It also improves compressive strength, the bonding strength between particulates, aggregates and embedded steel, and improves resistance to abrasion.

Silica fume may form up to 12% of the mass of cementicious materials. Silica fume has a specific surface of 63,000 to 150,000 ft2/lb (13,000 to30,000 m2/kg).

The uniformity of silica fume can vary according to the chemical characteristics of the metal alloys being manufactured. Silica fume from up to four different furnaces is sometimes mixed together in an effort to provide a more uniform product. The effects on concrete of variations in the chemical properties of silica fumes from different furnaces are not well understood. The properties of silica fume concrete also vary with the different properties and amounts of the various water-reducing agents (plasticizers) that are typically used when silica fume is added to concrete. Because the huge surface area of silica fume uses more water and reduces workability, plasticizers and super-plasticizers are added to make concrete more fluid so that it can be placed and worked more easily.

Concrete is typically mixed at local batch plants before being trucked to a job site. Batch plants commonly have silos containing fly ash and often have GGBFS on hand. Permanent storage facilities for silica fume are less common.

A concrete batch plant with two fly ash silos

AGGREGATES

Aggregates are granular materials that include sand, gravel, crushed stone, river stone, and lightweight manufactured aggregates, and may occupy up to 75% of the concrete’s total volume. Since aggregates are less expensive than cement paste, they are added to concrete to help reduce costs. The properties of aggregates can have a significant effect on the workability of concrete in its plastic state, as well as the durability, strength, density, and thermal properties of the hardened concrete.

Where do aggregates come from?

Aggregates are heavy. Quarrying them in a central region and trucking them long distances is cost-prohibitive, so aggregates are generally quarried locally. This means that the mineral, chemical and physical properties are likely to be different in different areas, depending on the local geology. Minerals with different properties can react differently to chemical processes or conditions in concrete, so aggregates are one more constituent material of concrete that can have properties that vary.

Quarrying Aggregate

Aggregate quarry operations are similar to those used for quarrying stone for cement. The quarry pictured below, also located in Colorado, provides primarily granite aggregate for the asphalt paving and concrete industries.

The photo above shows a relatively new quarry being worked. The drilling rig is shown drilling the holes in which explosive charges will be set, while a truck is loaded with stone loosened by previous blasting. The truck will haul the stone to Crusher #1.

Older quarries have been worked longer, so they are deeper. This operation blasts in holes drilled 35 feet deep, as opposed to 80 feet at the limestone quarry. Here, too, blasting is performed by a subcontractor. This operation contains several quarries in addition to the processing area, so it is a large operation.

Above, a truck feeds Crusher #1, the first in a series of crushers that the stone passes through. This quarry produces 18 different aggregate products that vary in size from boulders to sand.

Looking directly down into Crusher #1, the size of the stone before it enters the crusher is visible. The stone is moving from left to right.

Crushing and sorting operations are monitored from a central control tower overlooking the operations area. The conveyor nearest the camera is moving the stone after processing by Crusher #1.

The photo above shows the view overlooking the operations area, and the controls and monitors.

This overview photo shows two additional crushers near the center. Despite massive amounts of stone being crushed, transported, pushed and dropped onto stockpiles, airborne dust was minimal.

Aggregate Size

Aggregates for concrete are generally divided into two categories: fine and coarse. Fine aggregates are generally natural sand or crushed stone, with most particles passing through a 3/8-inch (9.5-mm) sieve. Coarse aggregates generally range between 3/8- to 1-1/2 inches (9.5 mm to 37.5 mm) in diameter. Most coarse aggregate used in concrete is crushed stone, although smooth river rock is also used.

Inadequate amounts of fine aggregates can cause excessive bleeding, difficulties in pumping concrete, and difficulties in achieving smooth troweled surfaces. The bond strength of fine aggregates is not affected much by the shape or texture of the aggregate, since smaller particles offer a large amount of surface area at which bonding to the cement paste can take place. The surface properties of fine aggregate can affect the amount of water required to keep concrete workable. Bear in mind that excessive amounts of water can weaken concrete by increasing the percentage of capillary structure left behind as excess water finds its way to the surface as bleed water and then evaporates. The photos below show aggregates commonly stocked by concrete batch plants.

1½-inch gravel

¾-inch gravel

Squeegee

Lightweight

Common sand

Double-washed sand

The maximum size of aggregate should be less than one-fifth of the narrowest dimension between the sides of forms, one-third the depth of slabs, or three-fourths of the minimum clear spacing between reinforcing bars.

Using the largest possible aggregate size is sometimes recommended to minimize the amount of cement required, as well as to minimize drying shrinkage of the concrete. The disadvantage of using large, coarse aggregate is that it increases the chances of bond failure between the aggregate surface and the surrounding cement paste, since the stresses at the interface between the two materials are higher than with smaller aggregate. It also reduces the total available surface-bonding area.

The rigidity/deformation characteristics of the aggregate are also important. Extreme differences in the properties of aggregate and cement paste result in high stresses that create micro-cracks that can weaken concrete.

Grading Aggregate

Well-graded aggregate is the result of using many sizes of aggregate in the mix. This helps reduce the amount of cement paste required to fill the spaces or voids between the individual aggregate pieces. Reducing the percentage of cement paste in the mix helps reduce shrinkage and lowers the heat of hydration, both of which can crack concrete. It also improves its durability. The amount of aggregate used in a mix is called its packing density. Well-graded aggregate has better packing density than gap-graded aggregate. Gap-graded aggregate has no intermediate-sized pieces, which makes the concrete more difficult to place and increases its cost, and both of these factors can affect the final product.

Moisture Content

Different types of aggregate have different levels of porosity; that is, they can absorb different amounts of water. Highly porous stone affects concrete differently, depending on whether it is water-saturated or dry before being added to the mix. Dry stone will absorb more water from the mix, and this can make concrete stiffer and more difficult to work, which may appear as visible problems in the finished concrete. Water in saturated stone has to be considered when calculating the amount of water to be added to the mix or the water ratio may be too high, resulting in weakened concrete.

There are four moisture levels:

- Oven-dry (OD) means that all moisture has been removed.

- Air-dry (AD) means that surface moisture has been removed and internal pores are partially full.

- Saturated surface-dry (SSD) means that the surface moisture has been removed, and all internal pores are full.

- Wet means that pores are full, and there is a surface film.

Of these four states, saturated surface-dry is considered the best moisture state. With SSD, the aggregate is in a state of equilibrium, so the aggregate will not absorb or give water to the cement paste. However, this moisture state can be difficult to obtain.

Lightweight Aggregates

A facility for manufacturing lightweight aggregate

Lightweight aggregates are typically man-made and are highly porous. Clay, shale and slate will expand when they are heated, a little like popcorn. Since most are porous, they are also moisture-absorbent, which can affect the amount of water used in the mix. A few types develop a coating during the fusion process that reduces their absorptive properties; however, if this coating is damaged during handling, the aggregate as a whole will regain some of its ability to absorb water. Depending on the percentage of aggregate that has damaged coating, this condition can affect the quality of the concrete if such a variation is not allowed for in designing the mix.

Heavyweight Aggregates

Heavyweight aggregates are usually used in buildings requiring radiation shielding and are not of concern to most inspectors.

Waste Materials as Aggregate

Many ideas for re-purposing waste materials have been considered and some have been tried. Inspectors may encounter concrete with problems caused by materials inappropriately substituted for aggregate.

Some of those waste materials include:

- building rubble;

- industrial waste; and

- mine tailings.

Alkali-Aggregate Reaction (AAR)

ASR-damaged concrete

Some types of aggregate materials react badly with alkalis from sources in the concrete or from other sources, such as de-icing salts, groundwater, or sea water. If the aggregates contain a large percentage of silica, the reaction is called alkali-silica reaction (ASR). If the aggregate consists of dolomitic carbonate rocks, it is called alkali-carbonate reaction (ACR).

During ASR, which is the more common of the two problems, soluble silica in the aggregate reacts with soluble alkali to produce an alkali-silica gel. When this gel absorbs moisture, it expands, causing concrete to crack. It may take a while after the concrete is placed for ASR to appear. Cracks in control joints, shrinkage cracks, or micro-cracks in the surface that are enlarged by freezing may allow moisture to enter the concrete and be absorbed by the gel. Some aggregates are non-reactive and others are reactive to varying degrees.

There is no cost-effective method for mitigation of concrete damaged by AAR. Correction requires removal and replacement.

Other Aggregate-Related Problems

- Some types of stone used for aggregates may cause problems by expanding and contracting during freeze-thaw cycles due to moisture content.

- Aggregates can vary in their resistance to wear.

- Aggregate impurities consisting of fine, solid particles can interfere with the surface bonding between cement and coarse aggregate.

- Aggregate impurities that are soluble may interfere chemically with alkaline cement pastes and affect setting times.

- Aggregate from quarries in coastal locations should be cleaned to avoid salt contamination that may affect the concrete chemically or attack embedded steel.